Batuku and Finason

Gláucia Nogueira and Graham Douglas

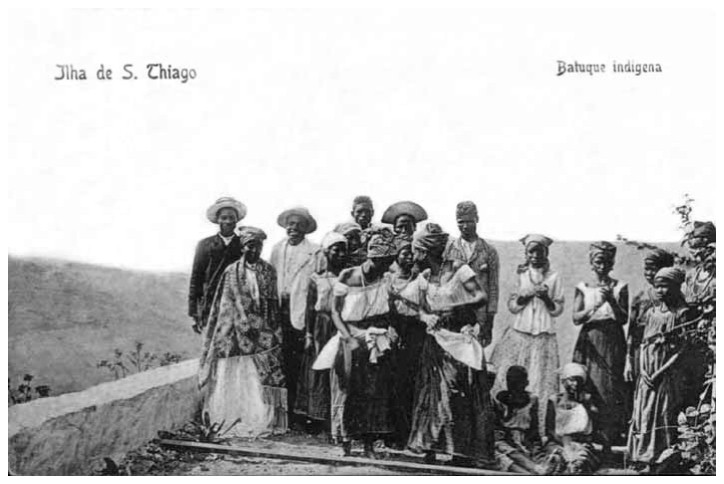

What is currently known as Batuku can be considered the oldest Caboverdean musical genre, originating with the music and dance brought to the archipelago from the fifteenth century, when the islands were populated by slaves from West Africa, beginning on the island of Santiago. Its polyrhythmic structure and performance based on call-and-response are common on the African continent.

Batuku is an icon of Santiagoan Badiu culture. The name Badiu has its origin in the pejorative Portuguese word “vadio”, meaning “a loafer, a layabout” which was applied to free blacks who had escaped the control of the colonial administration. After independence in 1975, overturning the stigma of this designation, the residents claimed the word as a statement of identity in Santiago.

A batuku session involves a group of percussionist-vocalists, usually women, who sit in a circle when playing in informal situations or in a semicircle when on stage. Performers sing, clap hands, and play percussion, sometimes on a drum, or on an instrument that they hold between their thighs. Nowadays the instrument is a synthetic leather cushion, but in the past, it was a rolled-up cloth or simply the performer’s legs.

In general, the session begins with a slow tempo and, as the song progresses, a part of the group initiates another rhythm at a faster tempo and rhythmic density, then another. This performance structure of the percussion based on three different rhythmic patterns of increasing intensity and density is called a xabeta, which is also the name of the instrument, a cushion that they play on. Some groups also use some type of drum.

Accompanying the percussion, there are usually one or more soloists who take turns leading the others who then respond with a chorus. During the first minutes of a batuku performance the song text is repeated. Someone begins to dance by moving slowly to the music, gradually picking up energy. It moves to a section during which everyone repeats one short musical phrase over and over until the song gradually winds down to a stop. This part of the xabeta is called the rapica, which is characterized by the repetition of a short melodic fragment (chorus) and a faster tempo. At the same time, one or two dancers perform dá ku torno, a dance concentrated in the lower torso and legs. The back, shoulders, and head remain almost motionless.This moment is the point of highest energy in the performance.

In the past, batuku performances used to be performed in two sections, the first part described above, is called the sambuna (and has a more playful and rhythmic character), and used to be followed by the finason (based on maxims and educational proverbs, characterized by improvisation). Nowadays performances consist of the sambuna alone. There are no more improvisers like Nha Bibinha Cabral or Nha Nácia Gomi, who were famous in the past for developing the finason.

When Charles Darwin passed through Santiago on his voyage aboard The Beagle, he witnessed one of these performances during a day of celebration in the locality of São Domingos (near the capital, Praia). He vividly described the scene and the group of about twenty young women welcoming the foreigners. They were “dressed in excellent taste, their black skins and snow-white linen being set off by colored turbans and large shawls”, wrote Darwin.

“(…) they suddenly all turned round and covering the path with their shawls, sung with great energy a wild song, beating time with their hands upon their legs. We threw them some vintems [coins], which were received with screams of laughter, and we left them redoubling the noise of their song.”

Charles Darwin in The Voyage of the Beagle, 1839.

Batuku was repressed during the colonial period by the Catholic Church because of the sensuality of its dance and by the Portuguese administrative authorities and due to the alleged disorder of these festive moments, when people drank a lot and sometimes there were fights. In general, expressions of popular culture were undervalued and repressed by the colonial power as a means of controlling the population. Moreover, in the colonial period there was a general social construction of stereotypes that opposed the northern region of the archipelago, Barlavento, considered as more Europeanized, to the island of Santiago, identified as the closest to Africa and therefore viewed in a prejudiced and derogatory way, as “wild”, “primitive”.

Following the independence of Cabo Verde in 1975, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cabo Verde (PAIGC) began to encourage popular traditions, and groups of batukaderas proliferated. Batuku is no longer restricted to the interior of the island of Santiago. The rural exodus at the time led to the appearance of groups in the capital and, with increased migratory flows, across Caboverdean communities in several countries.

In the early 2000s, urban musicians reworked batuku, taking its rhythmic patterns and transposing them to the guitar. In this case, the collective creation and improvisation was replaced by professional songwriters and a market for recorded music. Orlando Pantera, Tcheka and Princezito stand out among this new trend, along with women singers like Lura and Mayra Andrade.

For their part, traditional groups continue to proliferate, sometimes recording with the accompaniment of string instruments and keyboards. In some of them, there is also the use of the djembé drum combined with percussion on drum pads.